| What are we doing?

August 9th, 2003  I kept my word, this year. Which turned out to be easier, than I thought. Did I not feel jitters, these days? Did I not want to take part in this, the most fearsome event of our marching season, after all? Had I no urge to again throw myself unto those dusty, sunbeaten sandtrails? No! No! Triple no! In fact, the fact that, in the end, I managed to fulfill my intention not to go and walk the Death March in Bornem this year, but instead to render support to those marchers of the Wandelsoc. who dìd give it a try this year, ensured I had an outing to Belgium that was so relaxed, and experienced a satisfaction so deep that, during that Friday and Saturday, I was grinning almost incessantly. How happy I was, to be there, but not to have to march along, as I did in both 2000 and 2002. I kept my word, this year. Which turned out to be easier, than I thought. Did I not feel jitters, these days? Did I not want to take part in this, the most fearsome event of our marching season, after all? Had I no urge to again throw myself unto those dusty, sunbeaten sandtrails? No! No! Triple no! In fact, the fact that, in the end, I managed to fulfill my intention not to go and walk the Death March in Bornem this year, but instead to render support to those marchers of the Wandelsoc. who dìd give it a try this year, ensured I had an outing to Belgium that was so relaxed, and experienced a satisfaction so deep that, during that Friday and Saturday, I was grinning almost incessantly. How happy I was, to be there, but not to have to march along, as I did in both 2000 and 2002.

After all, we all know what this is about. This is the march nobody dares to undertake and all abhor, the march nobody wants to do, let alone multiple times, even though some do, the march that is only good to hàve walked - for wàlking it, is a dra-ma. There are marches that are even longer, like the Omloop of Goeree-Overflakkee; but there is no march that equals the doubtful but imposing style of the Death March. With its 100 kilometres from Bornem to Bornem, throught the Belgian Province of Antwerp, this is not just 1 of the ugliest, but also 1 of the most unpleasant marches that exist. There is hardly any public along the route, one cannot walk one's own regular tempo during the first hours, nobody is in a good mood, nothing takes away the boredom, the weather, be it raining or bloody hot, sucks, and the distance is of such inhuman proportions that at the end of it your hair aches, and you have a totally new conception of distances. Where in Nijmegen you think "Oh God, another thirty kilometres!", in Bornem you think "Ooooh, only forty k to go". Things like that. Hor-ri-ble. After all, we all know what this is about. This is the march nobody dares to undertake and all abhor, the march nobody wants to do, let alone multiple times, even though some do, the march that is only good to hàve walked - for wàlking it, is a dra-ma. There are marches that are even longer, like the Omloop of Goeree-Overflakkee; but there is no march that equals the doubtful but imposing style of the Death March. With its 100 kilometres from Bornem to Bornem, throught the Belgian Province of Antwerp, this is not just 1 of the ugliest, but also 1 of the most unpleasant marches that exist. There is hardly any public along the route, one cannot walk one's own regular tempo during the first hours, nobody is in a good mood, nothing takes away the boredom, the weather, be it raining or bloody hot, sucks, and the distance is of such inhuman proportions that at the end of it your hair aches, and you have a totally new conception of distances. Where in Nijmegen you think "Oh God, another thirty kilometres!", in Bornem you think "Ooooh, only forty k to go". Things like that. Hor-ri-ble.

Nah, I'd rather plan the support. That, in itself, was a drama of sorts too, but that wasn't due to the planning itself, but to van der Schelden MA. Van der Schelden MA, namely, is a controlfreak. What he has not arranged, cannot have been arranged, and therefore must after all be arranged by him. That is how things are arranged, in the world in which van der Schelden MA lives. And so that, beforehand, I had, with Max, thought up that Max and I would be along the route with a car full of food and drink, that I would not get away with just like that. When I hadn't even begùn thinking about the practical side of one and the other, van der Schelden MA sent me loads of mail with plans on his part, and worried questions about things that weren't his, but my problem. This culminated in a mail to the Wandelsoc. in which he announced that support would be rendered by Messrs. Neumann, van Reenen and possibly Max. So there's me wondering why Neumann was on there at all, and why the word 'possible' applied to Max. Nah, I'd rather plan the support. That, in itself, was a drama of sorts too, but that wasn't due to the planning itself, but to van der Schelden MA. Van der Schelden MA, namely, is a controlfreak. What he has not arranged, cannot have been arranged, and therefore must after all be arranged by him. That is how things are arranged, in the world in which van der Schelden MA lives. And so that, beforehand, I had, with Max, thought up that Max and I would be along the route with a car full of food and drink, that I would not get away with just like that. When I hadn't even begùn thinking about the practical side of one and the other, van der Schelden MA sent me loads of mail with plans on his part, and worried questions about things that weren't his, but my problem. This culminated in a mail to the Wandelsoc. in which he announced that support would be rendered by Messrs. Neumann, van Reenen and possibly Max. So there's me wondering why Neumann was on there at all, and why the word 'possible' applied to Max.

By itself, it was namely clear to me why the latter was so: Max's mother had, as fate would have it, been robbed, shortly before, by a junkie, and had broken limbs in the process, and so Max had told me he wasn't sure he could come along, shortly before - but towards Schelden the both of us had done nothing else than state that the two of us would render support - and I had, on purpose, agreed with Max that I would only ask him for his decision on the day before departure, so that he could use all his time and attention to take care of the motherly matter; so when Schelden rang him in panic, to ask whether he was still coming along, about a week in advance, and Max thereupon replied with a tired "No", I didn't only, justly, as it later turned out, ignore that, but I also got very angry, because of this pushy behaviour on Schelden's part. By itself, it was namely clear to me why the latter was so: Max's mother had, as fate would have it, been robbed, shortly before, by a junkie, and had broken limbs in the process, and so Max had told me he wasn't sure he could come along, shortly before - but towards Schelden the both of us had done nothing else than state that the two of us would render support - and I had, on purpose, agreed with Max that I would only ask him for his decision on the day before departure, so that he could use all his time and attention to take care of the motherly matter; so when Schelden rang him in panic, to ask whether he was still coming along, about a week in advance, and Max thereupon replied with a tired "No", I didn't only, justly, as it later turned out, ignore that, but I also got very angry, because of this pushy behaviour on Schelden's part.

This, coupled with his triple daily telephonades in my direction, drove me crazy even before I asked him why Neumann was listed in that email, as an attendant. So when he then said "Yes, Neumann is driving, didn't you know?", I exploded. By way of an angry mail I put the choice to him: either shut his gob and let me organize it, or do it all himself. He chose the first, thankfully, and because I felt his plan to combine support and transport of the marchers (for this was in that email as well: the declamation that the marchers would be picked up from and returned to home by a Wandelsoc.-bus, of which, at the moment that was written, I knew nothing), which was only passed on to me at the time of that phonecall about Neumann, was not so bad in itself, I went along with that. This, coupled with his triple daily telephonades in my direction, drove me crazy even before I asked him why Neumann was listed in that email, as an attendant. So when he then said "Yes, Neumann is driving, didn't you know?", I exploded. By way of an angry mail I put the choice to him: either shut his gob and let me organize it, or do it all himself. He chose the first, thankfully, and because I felt his plan to combine support and transport of the marchers (for this was in that email as well: the declamation that the marchers would be picked up from and returned to home by a Wandelsoc.-bus, of which, at the moment that was written, I knew nothing), which was only passed on to me at the time of that phonecall about Neumann, was not so bad in itself, I went along with that.

And so it was, that Marco Neumann came to bivouac at my place, on the night of August the 7th, and we set out together the next morning to pick up the 9-seater Ford Transit (airconditioning and all!) that we were to rent, at Bouwens Car Rental, around the corner. Shortly after, the company grew to include, as expected, Max, and Erik Kuijken, former secondary schoolmate who, following some years of radio silence, had become a good friend for some time now, and who has nothing to do with walking but, in reply to my invitation thereto, thought it would be fun to join in the rendering of support, armed with his well-maintained and surprisingly outfitted LandRover. Once our quartet had been expanded with Death March Grandmaster Johan van Dijk and marcher Fred Regts, both travelled to Haarlem from more northern parts of Holland, we took our convoy of 3 cars (for we also took along Neumann's own Redford), to Amsterdam. There, we stocked up at the Makro, for which, being a fresh enterpreneur I after all had a card by now (and we were phoned here, by Jasper Nales, who was not in our company, but who was also travelling towards Bornem, to partake of this bloody thing with Ralphie). And so it was, that Marco Neumann came to bivouac at my place, on the night of August the 7th, and we set out together the next morning to pick up the 9-seater Ford Transit (airconditioning and all!) that we were to rent, at Bouwens Car Rental, around the corner. Shortly after, the company grew to include, as expected, Max, and Erik Kuijken, former secondary schoolmate who, following some years of radio silence, had become a good friend for some time now, and who has nothing to do with walking but, in reply to my invitation thereto, thought it would be fun to join in the rendering of support, armed with his well-maintained and surprisingly outfitted LandRover. Once our quartet had been expanded with Death March Grandmaster Johan van Dijk and marcher Fred Regts, both travelled to Haarlem from more northern parts of Holland, we took our convoy of 3 cars (for we also took along Neumann's own Redford), to Amsterdam. There, we stocked up at the Makro, for which, being a fresh enterpreneur I after all had a card by now (and we were phoned here, by Jasper Nales, who was not in our company, but who was also travelling towards Bornem, to partake of this bloody thing with Ralphie).

And with those supplies we then drove to the Van der Valk-hotel in Breukelen. The Van der Valk-hotel in Breukelen? The Van der Valk-hotel in Breukelen. There, namely, Jochem Prakke arrived. Jochem Prakke? Jochem Prakke. He hadn't, you see, earlier in the morning, quite realized how early we wanted to leave, and therefore got into a serious panic when, in reply to his question at what time I planned to leave, I said: "Well, now. About half an hour ago, you see." "Jesus, but I have to go to and fro to Amsterdam yet." "To do what?" "To fix a leakage." "Well look here, that's not possible." "Yeah, but I didn't know you planned on leaving this early." "It was in the email I sent you." "But I haven't read my mail for a week and a half now." "Not my problem." We therefore agreed that Jochem would travel by hisself, from Amsterdam to Utrecht, there to join the rest of the pack, waiting in the Jaarbeurssquare. But his plan changed to a faster variant, and so, at the Van der Valk-hotel in Breukelen, he debarked from a small car, instead of getting out of a train in Utrecht. The pickup almost went awry, because Johan van Dijk, who was travelling along at the front of the convoy, in the Transit driven by Neumann, thought of his own accord that Jochem would then probably descend from the train to Utrecht in Breukelen, and I would therefore be feeble-minded, in ordering the convoy to stop at the hotel. No, sod! Do not think! Do as I bloody well tell you to! And with those supplies we then drove to the Van der Valk-hotel in Breukelen. The Van der Valk-hotel in Breukelen? The Van der Valk-hotel in Breukelen. There, namely, Jochem Prakke arrived. Jochem Prakke? Jochem Prakke. He hadn't, you see, earlier in the morning, quite realized how early we wanted to leave, and therefore got into a serious panic when, in reply to his question at what time I planned to leave, I said: "Well, now. About half an hour ago, you see." "Jesus, but I have to go to and fro to Amsterdam yet." "To do what?" "To fix a leakage." "Well look here, that's not possible." "Yeah, but I didn't know you planned on leaving this early." "It was in the email I sent you." "But I haven't read my mail for a week and a half now." "Not my problem." We therefore agreed that Jochem would travel by hisself, from Amsterdam to Utrecht, there to join the rest of the pack, waiting in the Jaarbeurssquare. But his plan changed to a faster variant, and so, at the Van der Valk-hotel in Breukelen, he debarked from a small car, instead of getting out of a train in Utrecht. The pickup almost went awry, because Johan van Dijk, who was travelling along at the front of the convoy, in the Transit driven by Neumann, thought of his own accord that Jochem would then probably descend from the train to Utrecht in Breukelen, and I would therefore be feeble-minded, in ordering the convoy to stop at the hotel. No, sod! Do not think! Do as I bloody well tell you to!

So as, aseven, we arrived in the Jaarbeurssquare, and there walked into the coffeeshop where Peter Weij, Jan Middelkoop and van der Schelden MA were drinking coffee, this therefore was my commentary in the direction of the latter. "How's it going?" "Badly! I've got people with me who think, all by themselves! They should not! We are, goddammit, a self-respecting, paramilitary, neofascist scouts club yes?! And there is no room for freethinkers in it!" Hilarity aplenty: he who wishes to stand tall, should take the piss out of himself. After Weij and Regts had feasted on the female game freely galloping about, we then repacked into the Transit, and stashed Neumann's Redford, which after all turned out to be superfluous, in InterPay's multi-storey parking. So as, aseven, we arrived in the Jaarbeurssquare, and there walked into the coffeeshop where Peter Weij, Jan Middelkoop and van der Schelden MA were drinking coffee, this therefore was my commentary in the direction of the latter. "How's it going?" "Badly! I've got people with me who think, all by themselves! They should not! We are, goddammit, a self-respecting, paramilitary, neofascist scouts club yes?! And there is no room for freethinkers in it!" Hilarity aplenty: he who wishes to stand tall, should take the piss out of himself. After Weij and Regts had feasted on the female game freely galloping about, we then repacked into the Transit, and stashed Neumann's Redford, which after all turned out to be superfluous, in InterPay's multi-storey parking.

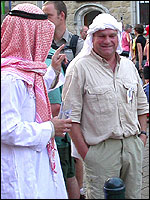

Then we caught De Gisser, Raymond, in Den Bosch, on a dumbfounded terrace, and from there we sped, via a smotheringly hot Antwerp (this did not bother the boys in the Transit all too much, despite Max' attempts to sabotage the airco by keeping a window open, but Erik and I were frying up in the open LandRover) and Boom, to Bornem, smoking cigars and consuming Red Bull by the tray. In Bornem, The Deathmarch turned out to have grown, and we therefore had to park a lot further from the city centre than usual, on a small grassy lot in a suburb. Having smeared the marchers' limbs with uddersalve (the hard way of learning for the long distance marcher, that turns them into the wise: if, between buttocks, in the crotch, on the nipples and behind the shoulders one does not apply a layer of this stuff, one bleeds after 60 km, in all those places, because they're scoured into open wounds), we then stepped through Bornem, to Bornem. There, on the square by the inscription tent, we met up with Harm Swarts and cousin Anne-Jan Telgen, who'd travelled down here by means of their own. With them, we usurped a 13-a-dozen-dinner in a tent of the local footballclub, behind the already overly filled terrace and interior of 'Het Land van Bornem'. This dinner, Schelden illuminated with a speech that was breathlessly listened to by all of us, about the colour politics of the medalmakers in question, as Jan Middelkoop was rightly and utterly amazed at Jochem's irregular dress: he was wearing numberless double yearpacks of marching ribbon.  Dinner behind the molars, we returned to the square, where we made obligatory sponsor-photographs of us in the Job- and AutoTrack-windcheaters, placed at our disposal by my employer, for the dark hours of the early Saturday morning, when chill and fatigue demand their shivering toll (that sponsoring, by the by, was, in these economically worse times, aptly more meager than in 2000, when besides the windjammer I also got a cap against the blistering heat on Saturday during the day - I could forget about that this year, and those jackets, moreover, were to be returned, at the end), and sat down on and besides the packed terraces. There, apart from a hilarious happening on Schelden's part, who donned a djellaba and Arabic headdress, then to take humorous pics with the jewishly dressed Max and fellow teatowel Harm ("What do you mean, odd? Where I come from they all wear this!"), and of the amusing GSM-synchronizing by the former commandoes, the thing that always happens, around that time in Bornem, again happened: the audience becomes noisier, the marchers become silent and grim, in the runup to the final minutes before the start. Dinner behind the molars, we returned to the square, where we made obligatory sponsor-photographs of us in the Job- and AutoTrack-windcheaters, placed at our disposal by my employer, for the dark hours of the early Saturday morning, when chill and fatigue demand their shivering toll (that sponsoring, by the by, was, in these economically worse times, aptly more meager than in 2000, when besides the windjammer I also got a cap against the blistering heat on Saturday during the day - I could forget about that this year, and those jackets, moreover, were to be returned, at the end), and sat down on and besides the packed terraces. There, apart from a hilarious happening on Schelden's part, who donned a djellaba and Arabic headdress, then to take humorous pics with the jewishly dressed Max and fellow teatowel Harm ("What do you mean, odd? Where I come from they all wear this!"), and of the amusing GSM-synchronizing by the former commandoes, the thing that always happens, around that time in Bornem, again happened: the audience becomes noisier, the marchers become silent and grim, in the runup to the final minutes before the start.

Back on the grassy lot in the suburb (absolutely won-der-ful, to nòt be packed together in the starting square below that-flying-parathing-that-mopeds-around, for a change!), where Erik had retired unto his LandRover for a bit longer already, we had a cup of coffee, and I restashed supplies, in order to be able to reach them quickly, before we determined a first resting point on the badly copied topographic map, in Wintam, and set off towards it as a convoy. Back on the grassy lot in the suburb (absolutely won-der-ful, to nòt be packed together in the starting square below that-flying-parathing-that-mopeds-around, for a change!), where Erik had retired unto his LandRover for a bit longer already, we had a cup of coffee, and I restashed supplies, in order to be able to reach them quickly, before we determined a first resting point on the badly copied topographic map, in Wintam, and set off towards it as a convoy.

We arrived there just before dark and, in a sidestreet just off the course, next to a funeral parlour (handy, because of its toilets) which had been completely rented by Marching Club De Schorrestappers (the name means 'Mudflat Marchers'), parked the cars, some 24 km from the start. As Erik made coffee and Max took turns with Marco in sitting by the course waiting to welcome our marchers, I cut them fruit (apple and orange parts), and arranged Red Bull, AA Isotone, Coke and napkins for them. Meanwhile, we drove the neighbouring marching clubs to insanity by playing the Wandelsoc.-song (sneakily burned onto CD before we left), so much so that there were those who started repeating it.  When, from the darkness of night, our marchers surfaced shortly after one another, they were in excellent shape, though complaining about the crowdedness which, particularly in the first round of the large 8-shape that the course is, led to ginormous congestion in a dark wood. In good spirits, they therefore nonetheless went onward, Jan Middelkoop and Raymond de Gisser bringing up the rear, after which we repacked for the treasure hunt to the next resting place. When, from the darkness of night, our marchers surfaced shortly after one another, they were in excellent shape, though complaining about the crowdedness which, particularly in the first round of the large 8-shape that the course is, led to ginormous congestion in a dark wood. In good spirits, they therefore nonetheless went onward, Jan Middelkoop and Raymond de Gisser bringing up the rear, after which we repacked for the treasure hunt to the next resting place.

For by itself, Erik and I had thought this out rather nicely: staying inside the track, it should not be impossible to, topographic map in hand, reach spots along it, which we therefore sought between the official rests, so that we could provide our marchers with a factual extra, and that strategy worked out fine - but now had to be won the hard way. For the next point we wished to place ourselves in, lay shortly behind Breendonk, and the Duvel-brewery there, and the road from Wintam to it, ran via Liezele. And in Liezele, roadworks were under way. Which basically meant the road was gone, altogether. And so, after we had tried, utterly in vain, to ask an overly friendly, but also drunk Belgian for the way, a crazy puzzleride ensued, in an outflanking movement, largely by feeling and on compass, Maglite in hand above the badly readable copy of a topographic map, humping and bumping along unlit, narrow country lanes, LandRover in front, Transit behind it. For by itself, Erik and I had thought this out rather nicely: staying inside the track, it should not be impossible to, topographic map in hand, reach spots along it, which we therefore sought between the official rests, so that we could provide our marchers with a factual extra, and that strategy worked out fine - but now had to be won the hard way. For the next point we wished to place ourselves in, lay shortly behind Breendonk, and the Duvel-brewery there, and the road from Wintam to it, ran via Liezele. And in Liezele, roadworks were under way. Which basically meant the road was gone, altogether. And so, after we had tried, utterly in vain, to ask an overly friendly, but also drunk Belgian for the way, a crazy puzzleride ensued, in an outflanking movement, largely by feeling and on compass, Maglite in hand above the badly readable copy of a topographic map, humping and bumping along unlit, narrow country lanes, LandRover in front, Transit behind it.

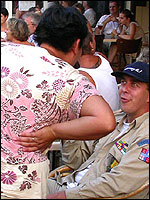

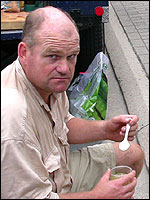

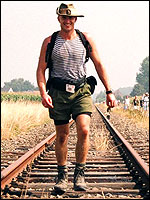

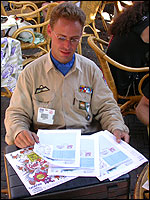

At the end of an impossible country road, however, we then finally reached the track. And as we almost constantly ran the risk here, of being driven down by local Belgians, who, in sedans and heavy trucks, unperturbedly kept on using this short cut to cut through the course, as if there was no Deathmarch, going about their daily, or rather nightly business, we neatly unpacked our supportive assortment once more, and Erik made coffee. Nevertheless, we did run into adversity here: for before the marchers arrived, Max fell ill. Seriously so, because his ulcer made him groan with pain. Thankfully, bread and water went some way to lessen it, and paracetamol, with which Weij supplied me when he arrived, did so even more. Weij, by the by, was working up a nice sweat by now, as were the others. Not so odd, we were at 42 kilometres from the start here, after all. Upbeat they all were to the utmost, though, and once they had relubricated the limbs, they then bravely threw themselves into the night again. It would be a long time, before we saw eachother again. That would namely happen the next day, in Buggenhout. And we got there very fastly, because we cut throught the lower round of the 8 in a straight line, about an hour and a half after we'd waved goodbye to our last marcher in Breendonk. And as they bravely made their way through kilometres of dark Belgium, towards dawn and the hot meal, around six in the Palm-brewery in Steenhuffel, we laid ourselves to rest in Buggenhout, in a sidestreet just off what we held to be the course. What we hèld to be the course. Since, once awakened, having consumed the eggs-on-salami, and having cut the fresh fruities for stock, we found out the course had been waylaid this year, and we had to move LandRover and Transit two streets further up, at a snail's pace, because we'd already displayed supplies on the upper deck of the LandRover, hoping still to be on time to catch our marchers. We succeeded: we not only were in ample time to receive them, but also to welcome Henk de Rooy who was doing a piece on fellow citizen Anne-Jan Telgen's Deathmarch-achievement, being chief editor and journalist of the local newspaper in Lunteren himself, and who therefore joined us here. In doing so, he was able to witness the emotional reunion with our heroic marchers. For such it was, logically, after such a long night and 72 kilometres bravely stamped away. And they had totally had it. This did not just shine through in the growingly resounding despair in their phonecalls to us ("Where are you at?" "Is it a long way yet to where you are?"), but also in the relief of their collapse on arrival. As it now slowly became unmercifully hot, in between the dusty country roads, and I supplied everyone with rolls of liquorice to counter the rapid loss of salt that came with that heat, Raymond de Gisser had Erik put icecubes, lent from a friendly Belgian neighbour, on his left shin, the one that was already plagued so much in Diekirch, Harm Swarts, an exasperated expression on his sweaty face, told me it was "a BAD moddafokka of a march" (tell me something I don't know), Fred and Peter, in silence, threw themselves unto soup produced from Erik's LandRover, Jochem Prakke fell over backwards into the Transit and murmured things about giving up that made us forget even his legendary lament about busstops on the Afsluitdyke, and even Grandmaster van Dijk looked at me grimly, and somewhat astonished on the fringes. The only one who actually was doing unexpectedly well, was Jan Middelkoop. But then, he was happy enough to be able to walk at all, of course, following his tragic withdrawal-due-to-backache, in Nijmegen. And this is how it is, men. Although Nijmegen most definitely is a heavier march than the Death March (because, at the end of the Death March, one can fall over, but in Nijmegen one has to repeat the feat up to four times), the Death March remains to be the Deathmarch: a Godforsaken, terrible thing. That deathhead must be earned.  As our friendly Belgian neighbour heartily agreed. He'd done it twice himself, so he knew what he was talking about, as he spoke about it all in a respectful manner, to Henk de Rooy, Erik, Marco and myself, and we thanked him with cigars for his sons, and bid him farewell after we'd photographed his garden gnome, before, with a Death March organisational sign, stolen by Erik from a roadblock, tied to the front bumper of the LandRover, we cut right through the track and to Oppuurs, via Puurs. This, too, went fast, so that we had ample time to position ourselves, by the roadside, at three quarters of the killing railroad track behind Oppuurs, under a treeline that provided us with some shade. As our friendly Belgian neighbour heartily agreed. He'd done it twice himself, so he knew what he was talking about, as he spoke about it all in a respectful manner, to Henk de Rooy, Erik, Marco and myself, and we thanked him with cigars for his sons, and bid him farewell after we'd photographed his garden gnome, before, with a Death March organisational sign, stolen by Erik from a roadblock, tied to the front bumper of the LandRover, we cut right through the track and to Oppuurs, via Puurs. This, too, went fast, so that we had ample time to position ourselves, by the roadside, at three quarters of the killing railroad track behind Oppuurs, under a treeline that provided us with some shade.

A wonderful spot, for multiple reasons. Firstly, because of that shade, and the quiet that this country road, to the left and off the course, but very close to it, offered. Secondly, because I, contentedly overviewing the laid-out resting area from the berm by now, was suddenly tapped upon the shoulder by someone of whose presence I had been forewarned even before we left the patch of grass in Bornem, by Raymond de Gisser, via SMS, but the sight of whose face nonetheless gave me an utterly pleasant shock: Steve Atkinson, flight lieutenant, Herts. and Bucks Wing, ATC. The only foreign team I have the honour and right to actually be part of, had looked forward to an appearance at the Death March for a long time now. And so now, it had finally come about: Andy Briant, friend and hero, was doing the Death March this year, along with some other air cadets, and Steve was here, to support them. It was to be a pleasant get-together, armed with the binoculars, in the sweltering heat at the head of the railroad track, looking past the endless line, for our respective marchers. See, that's another reason this place was so perfect, for a resting area: this endless stretch along the dusty railroad is the thing this march rightly earns its name by, and barring the last dyke towards Branst, it is the worst part of the entire Death March, and this crossing, at three-thirds of its way, is the per-fect spot for a cool, refreshing break. As, therefore, our marchers thought, past complaints by now, grimly growling in perseverance. Only Prakke was starting to slowly become his old self again. Now that pain and fatigue had taken on ridiculous form, Jochem no longer saw a reason for despair in them, and his mutt was already frightfully malformed again, by the well known broad grin that so clearly gives the emptiness of his skull away. This was different for the others, who, like Jochem, were provided with fruit and chocolate here by us, thankfully tumbling into the seats we had torn from the Transit, in shadow. But given the point in the course we were at (at 85 kilometres from the start) they were doing fine, and because of this, hope began to spark in me for what would later become reality: a glorious finish of all marchers, not one dropout among them. That finish, however, would pass without my presence, alas, because Max became ill again, here. So badly so, in fact, that I accompanied him, in an ambulance that had raced to the rescue, to St. Blasius General Hospital, in Dendermonde. There, while Max was being treated, I spent about an hour and a half in an uncooled waiting room, as between Branst and Bornem our marchers received support one final time, from Marco and Erik, and reached the finishtent in Bornem as victors. The medical staff announced Max would be unconscious for an unknown length of time yet, but would expectedly awake in resonable shape, and could then be taken home in an ambulance, at the expense of his health insurance. Bearing the fatigue of the marchers in mind, I therefore took a decision that I found difficult to, and left Max behind in Dendermonde. Picked up there by Erik, in his LandRover, we drove north via Antwerp until, at a gas station in Zundert, we met the rest for one final time, so that I coulde congratulate them, and we could take an utterly cool group shot (without Max, alas, and without Harm and Anne-Jan, who had already returned to the Netherlands by their own means), in front of the cars, in the fiery red afternoon sun, at the end of the longest day of the year: the day, of the Death March. And you will not hear me say this was due to our support (for that would be presumptuous, and there is room for improvement to that support, moreover: we have learned a lot, this first time over; no oranges but grapes, next year, no beer but tomato soup, drinkyoghurt to boot, coolboxes to stash the stuff in, and an extra stop at the Vomar first, so as to acquire a lot of things in apter amounts than the bulk the Makro confines itself to) - but it is a fact that in 2003, as the Academic Walking Society, we have, with 5 marchers of our own and 4 Friends Of, no dropouts, crossed the finishline of a stiflingly hot, ponderous edition of the Death March. And those satisfied mugs and raised glasses, during the afterparty in Haarlem, are etched into my retina as one of the most honourable things to befall me, this year. To your health gentlemen, ex-cel-lent walking there. The Yser awaits Schelden - the Airborne is ours. |